When I was 18, I remember thinking how lucky I was. Lucky to have been born into a loving, secure family; live in the best city in the world; be at a great school and going off to a great university (both free); and be coming of age at a time of relative peace, stability and great opportunity for women. (Plus, I’d once been in a lift with A-ha and had seen Phil Collins live). I was lucky, right?

Over 30 years on, I still feel lucky in many ways. Just not all.

Saturday 18 February 1989. Some time in the morning.

On a beach in Southport. It was February, the 1980s and I was 19, so I was in an oversized herringbone coat, chunky multicoloured jumper, jeans and DMs. Short curly hair growing up (yes, up) out of my head.

I was in Southport for the weekend with my cousin, Julian, and a gang of friends. We’d come over from Manchester where we were at university (I, in my first year of a law degree). Staying at Julian’s lovely family home and enjoying a reprieve from the breeze block walls of my student room and toasted sandwiches for every bloody meal.

I remember being worried about a contract law paper that was due in. I can’t remember why; maybe I was about to miss the deadline, or maybe I just didn’t know the answer. After a wander along the beach – when I’m pretty sure that I ignored the sea and the sky and the birds and the sounds and the smells, and just fretted about that stupid paper – we went back to the house.

In the house, coat still on. Stanley – Julian’s dad (and my mum’s cousin) – took me to one side and said that I needed to go and see my aunty and uncle in Preston (my dad’s sister and brother-in-law). Hmm, that wasn’t planned. I was thrown, but didn’t question it. We must have jumped straight into the car. My overnight stuff remaining in Southport, in my green Benetton duffel bag (of which I was tremendously proud).

A 40 minute or so car journey. Some small talk. There was something odd in the air, but I kept schtum.

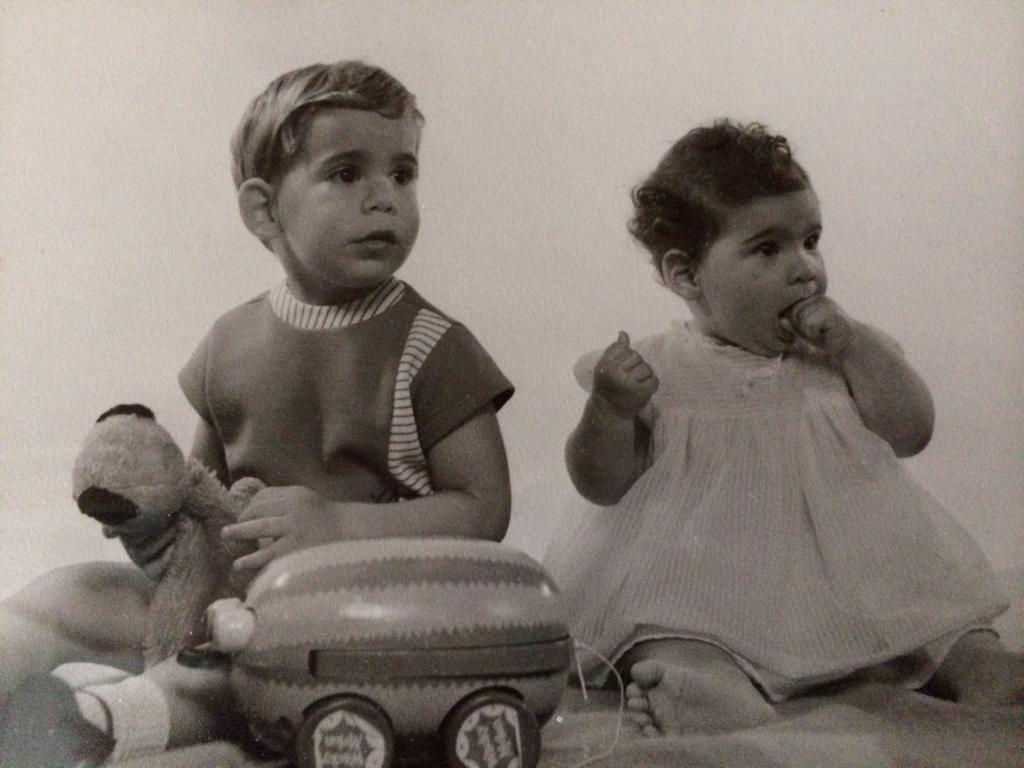

In Preston at my aunty and uncle’s house. Where I’d spent many happy summers with my brother Laurence and our cousins when we were kids, learning Beatles lyrics and playing cards. It was a lovely, familiar place to be.

Aunty Estelle came to the door. I smiled, she didn’t. She ushered me into the living room.

Aunty Estelle: Laurence died this morning.

I think I may have laughed.

I don’t remember much of what happened next. Even now, 31 years on, I am scared to call that time to mind, scared to feel what my 19 year old self was feeling. Somewhere inside, I am still resisting the truth of what happened. But what I do remember is a sensation: Of free falling. Into a black void, untethered to anything or anyone, tossed around, alone. Nothing made sense. Nothing.

But that wasn’t the worst of it.

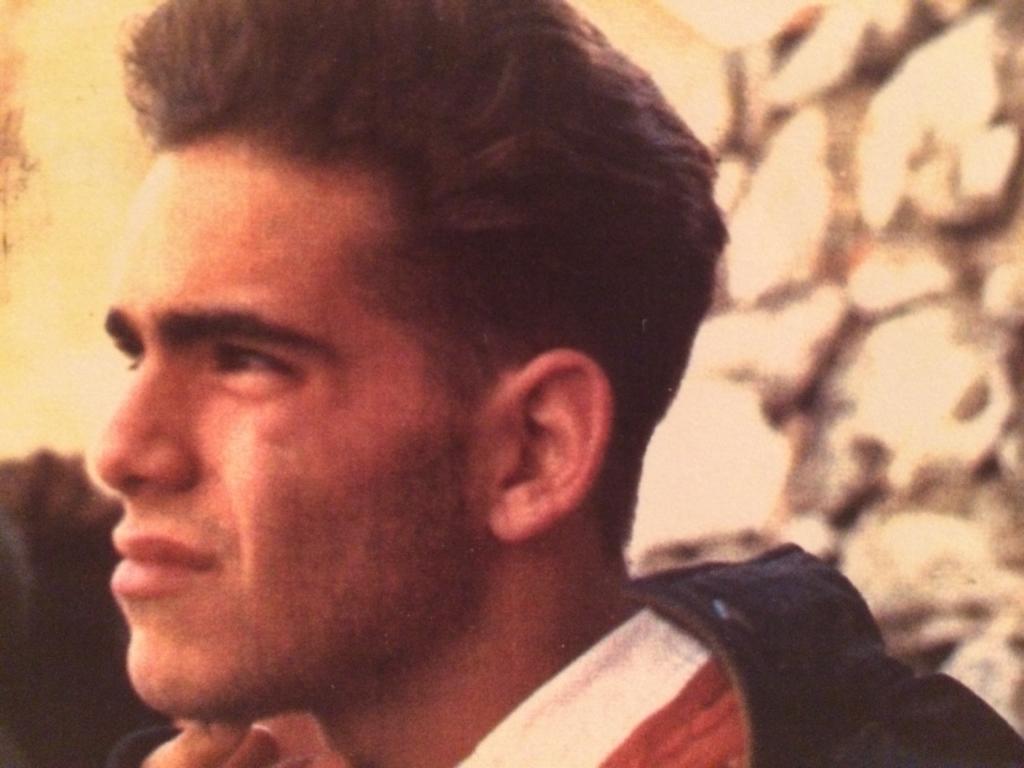

Laurence. My gorgeous, handsome, charming 20 year old brother. Barely 15 months older than me; I’d never known life without him. For a time, Laurence called himself – and insisted others call him – John, after John Taylor of Duran Duran, whom he resembled. He (Laurence) wore ripped jeans – before that was a thing that boys in Sutton wore – a leather jacket and a trilby. He was over 6 ft tall, had luscious dark hair, George Clooney eyes, legendary eyebrows and was devastatingly handsome. And charming. Get-away-with-murder levels of charm. He turned on his smile and everything was forgiven. Even if it was ALL HIS BLOODY FAULT. (I, on the other hand, was a charmless, shy, pudgy, swot, and much of the time, totally fucking hated him for it.)

Laurence was living at home with our parents, studying for A levels that he hadn’t taken the first time around. After taking time out, including a year in Israel on a leadership programme (the top photo is Laurence in Israel, towering above his friends), he had a place to study history at university starting that September. Just after his 21st birthday, which fell on 1 September 1989 (or would have done, had he lived to see it).

Friday, 17 February, 1989. Laurence was at home, with my parents, while I was in Southport. He and my parents ate dinner together. Before he went to bed, he chatted to his friend, Helena, on the landline. He was fine. Everything was fine.

Then it wasn’t.

My aunty and uncle drove me back to Southport to collect the Benetton bag. I don’t know if I spoke to anyone when I got to the house, but I vaguely remember feeling sad that I had to leave; sad about missing out.

The drive from Southport to Sutton isn’t fun at the best of times. This drive, at the worst of times: five hours or so, on a Saturday afternoon into evening, in February, in the dark and driving rain. Towards my home, our lovely family home where we’d lived since I was 5 years old. Towards the home where we had a bar in the hallway, swirly 70s carpets and a fish tank built into the wall. Towards the home where Laurence and I stole mum’s cigarettes and smoked them out of his bedroom window. Towards the home where my parents hosted their bridge group every few weeks and Laurence and I snaffled more snacks that we served, as we wandered around handing out crisps and nuts to the guests: the women, smoking cigarettes and gossiping in the living room; the men, smoking cigars in silence, in the dining room. Towards the home where we always had Friday night dinner together, and welcomed a houseful of family, friends – and often, strangers – for every Jewish festival. Towards the home where Laurence charmed the pants off anyone who walked over the threshold, while he and I fought like cats and dogs, mainly over possession of the TV remote control, and because he got away with FUCKING EVERYTHING. Towards the home where my lovely, sweet, anxious, mum, had found Laurence, her only son and first born, dead in his bed that morning. Towards the home to which my dad had rushed back from synagogue, having been called out due to an emergency at home. Towards the home where my parents (our parents?) were drowning in shock and grief, barely being held afloat by family and friends, waiting for their surviving child to return to them. Not only had I lost a brother, but they had lost their beloved son: That was the worst of it. That was where I was headed. That was the worst journey imaginable but I never wanted it to end.

Laurence had died in his sleep. Of what is sometimes referred to as sudden adult death syndrome. In his case, the cause was myocarditis: a virus that attacked his heart when he was asleep. Because he was asleep, he had no way of defending himself. When you hear about a young footballer or rugby player dying suddenly, the cause could be myocarditis. It is a terrible thing that can, and does, afflict (seemingly) healthy young people.

Friday night, he was here, all was fine. Saturday morning, gone.

And all of us who loved him: [I honestly can’t think of a word to do that feeling justice].

Things I’ve learned

Grief is not predictable, it doesn’t follow a set pattern, timeline, pathway. My grief and yours will look completely different. My grief when Laurence died was completely different to my grief when my dad died, 17 years later.

There are, though, some things that I think are common to most experiences of grief: It’s reassuring to hear stories of people who have experienced similar things to whatever it is you’re going through; hard as it may be at the time, it’s (probably) better to talk about it; and it takes time, you can’t rush it, but things will and do get better. The loss of a sibling – especially when young – brings other, complex, challenges.

On stories

As a bereaved 19 year old – unsurprisingly – I knew no-one who had been through anything similar, and I couldn’t find a book or story that resonated with me. I still search out stories of sibling death like a pig looking for truffles, always on the hunt for one – just one – that resembles my experience. There is something so reassuring and connecting in that shared human experience. Even now, 31 years on, I’m still hungry for those stories. That’s also why I wanted to tell my story, in case it helps, and to share some of the things that I’ve learned about grief along the way.

On talking about it

When Laurence died, I was 6 months out of school, no longer a child, but not yet an adult either. An adult child, maybe. I had no emotional or other qualifications for dealing with the sudden death of my 20 year old brother. They don’t teach you that in school, or anywhere, for that matter. I did get a letter from the university saying how sorry they were and allowing me time off. I think I was offered some counselling – I can’t recall from whom – but anyway, I didn’t take it. I was in no mood for talking. Within weeks, I was back in that breeze block student room, self-medicating with booze.

Needless to say, this strategy did not work out well for me, and while I wish I’d done things differently, even with the benefit of hindsight I can see that that was easier said than done.

One of the complications being this: The people to whom I would ordinarily have turned as a 19 year old, to support me through an unspeakably terrible thing, were my parents. That option is not really available when your parents are the only two people on the planet who are more broken than you are.

(And there’s a reason why bereaved siblings are sometimes referred to as ‘forgotten mourners’, as the attention of those supporting the family is generally aimed towards the parents and the sibling’s loss can be seen as less ‘significant’.)

Another, related, complication: I was dealing with my own grief, at the same time as witnessing that of my parents. Before Laurence died, I couldn’t bear it if my dad shouted at my mum for declaring the wrong suit in bridge. I HATED any discomfort or conflict, I just wanted everything and everyone to be ok. Witnessing my parents’ grief was unbearable, but I could not turn away from it. I had no choice but to face my parents – broken, hopeless, drowning – when I walked into the house after that terrible journey from Southport, and in the days and weeks that followed.

The one thing that I felt I could do to mitigate the awfulness of everything was to not ‘burden’ my parents with my grief. So I made my decision: I would not talk. I hid my feelings away in a steel box which I secreted in the furthest crevices of my mind, for many, many years. As much as it pains me to write this, I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of conversations that dad and I had about Laurence, in the years before dad’s death in 2006. I so wish it were different.

Not only did I not talk to my parents, I didn’t talk to my friends, either (I’m awarding myself points for consistency, at least…). Of course, now, I wish that I had allowed them to support me. Believe me, they tried. But there were so many reasons why it felt impossible at the time, not least because my main coping strategy was to tell myself that NOTHING WHATSOVER HAD HAPPENED, so there was nothing to talk about, right? (The suddenness of Laurence’s death, the absence of ‘evidence’ of his death – I didn’t see a body, there was no mashed up car, etc., – and the fact that we were living 200 miles apart when he died, enabled me to persist with this warped thinking for, well, many years).

On the very rare occasion, when I was alone late at night, and allowed myself to tiptoe tentatively towards that steel box of repressed feelings and memories hidden in my head, I could not get past the fact of Laurence’s death; I could think of him only as my dead brother. As a therapist wisely pointed out many years later, I had memorialised him in his death. And in doing so, spent years depriving myself of the memories that I had of him in life. He had lived a complete life, a short one, granted, but complete nonetheless. There was a beginning, middle and (abrupt) end. But I had written him out of history, expunged him, expunged our relationship. Maybe that’s also why I’m writing this now. To assuage my guilt, one word at a time.

In all of this, what I’ve learned is clear. If you can – actually even if you can’t – it’s better to talk. To anyone who’ll listen. Talk about the death of the person you’ve lost, but more importantly talk about their life. Look at photos, enjoy the memories, good and bad. Talk like your life depends on it. (Because it does.)

If you’re supporting someone who’s grieving, let them know that you’re there when they are ready to talk. Day or night. Now or in 31 years’ time.

And if you know or come across anyone who’s lost a sibling, please, be gentle.

On not avoiding the bereaved

One of the brilliant Jewish grief rituals is the shiva, a 7 day period of mourning that starts immediately after the funeral. During this time, the immediate family (the mourners) stay at home, and are looked after by friends and family. In my experience at least, this is a time when there’s an open invitation for, well, anyone really, to come to the house. You don’t wait to be invited. Many people bring food (without being asked). This ritual avoids all this awkward nonsense: ‘Oh I don’t know if they will feel like seeing anyone’, or ‘I don’t want to make it worse by mentioning it’. You go to the house. You sit with the mourners. You talk or don’t talk. You turn up. It’s the turning up that’s important. The mourners are held during this period by family, friends and community. If I’d had my way, the shiva would have carried on, and on. The hardest bit was when it was all over and people drifted away.

In the awful weeks and months that followed the shiva, one of the few things that provided succour to me and my parents was the on-going contact that we had with Laurence’s friends. There were few things that could raise a smile on my parents’ faces during that time, but seeing Laurence’s friends and hearing them tell stories about Laurence, was one of them. It brought Laurence closer to us; when his friends were in the room – with the same energy, language, humour as his – it felt like he was nearby, too.

What I’ve learned is this: Don’t stay away. Turn up. You don’t have to think of anything reassuring or novel or clever to say. You don’t have to say anything. The worst thing has happened, you can’t fix it, so don’t try. Just go, just turn up. Offer a shoulder. Take someone’s hand.

And a small, practical thing I’ve learned. Rather than asking a bereaved person: How are you? (because the answer will generally be: I feel like total crap), think about asking: How are you today?, instead. It’s a small change that can make a big difference.

On survivor guilt

This is tough to write about, but I suspect my experience in this is far from unique, so I’m going in. At the time Laurence died, I believed in G-d. Not so now, but that was then. I had always thought that there was some grand plan, that things happened for reasons. And the way that Laurence died – without notice, in the middle of the night – made me believe that he had been “taken”, for some reason. But I was confused; if anyone was going to be “taken”, why him? He was the most handsome, charming, popular of everyone. It made no sense. So this is what my mind came up with: It should have been me. No-one much would have missed me (so my thinking went). I was awkward and shy. I didn’t have half the personality, looks or charm of my brother. I wasn’t being primed to be a future community leader. I genuinely believed that my parents, given a choice, would have chosen for it to be me. My warped thinking – that went unchecked as I kept it all to myself – led me to develop a deep sense of guilt and shame that Laurence had died instead of me.

My guilt of being alive was twinned – ironically – with a profound fear of dying. In the aftermath of Laurence’s death, my parents held on to me – literally and otherwise – for dear life. Mum – poor mum – came to my bedroom early every morning to make sure that I was still breathing. When I eventually returned to Manchester, she called me every morning to check that I was still alive, which was not an easy feat as this was 1989, and we had one landline between 16 of us. To this day, mum and I speak daily, often multiple times a day, even when I’m abroad. These days though, it’s as much about me checking that she’s still alive, as it is her me.

Over time, I absorbed and integrated my parents’ fear of losing me. I believed that I could not die as they would not survive losing both of their children, so it was my duty to keep myself alive. That, I realise now, is fertile ground for health and premature death anxiety disorders, among other long-term psychological effects.

Had I talked to someone at the time, rather than keeping all of these complicated, conflicting, self-sabotaging beliefs to myself, I could have saved myself years of trouble – and therapy bills.

On the impact of sudden death

On top of dealing with our loss and grief when Laurence died, the suddenness of his death has also left its own, separate, legacy. My trust in, well, just about everything, disappeared on the day that Laurence died. If my fit, healthy, 6 ft tall, 20 year old brother could die suddenly, with no adequate explanation (as far as I was concerned), then anything equally bad could – and probably would – happen, at any time. So, my parents could die next week. My best friend could die the week after. And then maybe it would be me the week after that. My trust in the universe, and things turning out ok, died with my brother.

Over time, this fear of terrible things happening did subside, but it continues to have an impact. I worry more than the average person about bad things happening. I balk at unexpected phone calls, and don’t like opening letters or emails when I don’t know what’s inside (although to be fair, that can be quite a good email management technique these days).

If you’re ever planning to organize a surprise party for me, maybe let me know in advance (oh, and thanks).

On being asked if you have siblings

For many years after Laurence died, I used to scan conversations for the likelihood of the seemingly innocuous “do you have siblings?” question coming up. If I could sense it coming, I would make my excuses and scarper. But I didn’t always get out in time, and was then faced with a decision: Do I say no, and avoid the awkwardness (and deal with the terrible feeling of betrayal)? Do I say yes, and then hope I get no further questions? Or do I just tell the truth – but what if I don’t want to get into a conversation about it and BRING DOWN the mood?

What I’ve learned, is to say whatever feels right to me, which these days, is this: Yes, I have a brother (he died a long time ago). Because I do. I do have a brother.

On hope and the future: This too shall pass

During the shiva, I remember saying to someone that I would never laugh again. Never. My life was as good as over and that was that. That profound crippling pain of grief – the pain that prevents you from getting up in the morning – takes time to subside, there’s no rushing it, but even in those early days, there were moments of relief. Over time, those moments got longer and more frequent. And then one day – I don’t recall when or what about – I heard myself laugh.

This is probably the most important lesson I’ve learned over the years: Everything changes. This is as true of good times and good feelings as it is of terrible times and terrible feelings. None of it lasts forever. I have found this a great comfort.

In the 31 years since Laurence died, there have, of course, been some very dark periods. I’ve struggled with anxiety and panic attacks. Relationships have not come easy (I suspect the box of repressed feelings didn’t help). In my mid-30s, my lovely dad died a few weeks after taking ill unexpectedly. Mum has suffered with ill-health for many years. My life – by the measures by which many of us judge these things anyway (house, marriage, children, etc.) has not turned out the way I had ever expected (I drive a Skoda, for god’s sake).

But let me tell you this: I’m happy. Happier than many people I know, who have – on the face of it at least – been so much luckier than me. My anxiety and grief propelled me towards yoga, meditation and many and varied forms of therapy, coaching and self-discovery, all of which has taught me so much about happiness, love, compassion and self- care. I have an amazing group of friends and some very close family who have carried me through the darker times, and who – reluctantly or otherwise – danced with me through the night at my recent 50th birthday party. This is my story and not my mum’s, but mum and I have a better relationship now than we’ve ever had: Gentle, compassionate and loving. And every so often, we talk about Laurence. My gorgeous, charming, devastatingly handsome brother Laurence.

Now that makes me feel lucky.